It was half day through day one that I felt a ripple of relaxation shift through me. When the same thing happened the next day, I understood its source. I had given myself permission to write.

This three months of creative productivity wasn’t an easy thing to commit to. It has meant dropping out of full-time work, and a consequential drop in my income. I’m not money-focused, so the numbers aren’t important. But I place a huge value on harvesting experiences, some of which consume cash. Particularly the ones where I board a plane with a belly full of anticipation, and a thousand dollar ticket.

And of course I have bills to pay, a share in both a forest and a house truck to pay off. So I’m working in an office two days a week to cover all of this. And coffee. But parts of me have had to be put on hold.

I live in a country which is not given to celebrating the arts. Our statues are rarely of philosophers, or novelists, or painters. The result of this is that patrons are few, novelists are rare, and “suffering” for your desire to create isn’t generally understood. And so the decision to simply write takes a combination of self belief, considerate friends, and a supremely understanding partner.

So as much of a thrill it has been to let my imagination draw me forward, I have also had to plan to make my writing a business. It’s a confronting realisation. As much as this 88 days is going to be about generating stories, it is going to have to equally be about self-promotion. I don’t have an agent, nor a publisher. I don’t yet have a track record of works printed in The New Yorker, or Granta. I need to earn my own reputation.

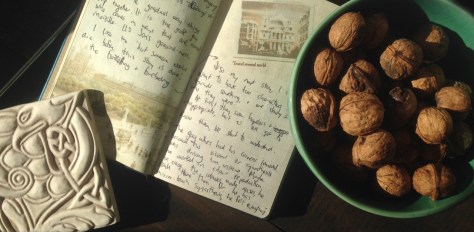

Writing is a quiet pursuit. Me, a keyboard or notepad. Maybe birdsong, or Lorde’s new album on a lower volume than it deserves. The world has no audible or visual clue idea that I’m unfurling scenery, painting characters, summoning mythology. For all they can see, my brow might simply be furrowing in lieu of Tinder responses.

When you practice with your heavy-grunge band, the world is alerted. A couple of beers, a wall of amps, and the wail of feedback, there’s no denying your output. When I painted murals around walls, an audience was assured, commentary was inevitable. But my words threaten to lie cold within the cage of my laptop. Colourless without a mind to project them, silent without a consciousness to voice them.

I heard a wonderful quote this week, though I failed to make note of the origin. Or the exact words. But it was something like “what a joy it is to remain hidden from the world, but what a crime it is, never to be discovered”. For five years I’ve remained largely silent about my stories. It’s time to start beating a drum. And over the past seven days, I’ve started to understand that I shouldn’t be beating it just for myself.

One of my tasks in week one, was a hunt for community. And what I’m finding, is that I need to be that community, as much as to find it. Once I find inspiration in someone’s talent, or tenacity, or imagination, then I need to make some noise for them as well. I can’t write as part of a band or troupe, but I know I can be an enthusiastic member of other people’s audiences.

So I sit in the shade of the seventh morning, listening to the thudding of my heart. I’m preparing to work not just on the foundations for my own success, but also to begin contributing to the elevation of others.

I think the two most transformative toys of my childhood were my bike, and Lego. The bicycle might earn a place in this list at some stage, but today I want to talk about magical Danish bricks.

I think the two most transformative toys of my childhood were my bike, and Lego. The bicycle might earn a place in this list at some stage, but today I want to talk about magical Danish bricks. The old man is initially defined by the curve of his spine. He’s bent almost double by some malady, and I feel the warm prickling of guilt as I watch him roll one sleeve up, and look over his shoulder. But I’m over the other shoulder, at a window seat in a busy cafe with another dozen pairs of averted eyes. He tilts his body like a crane and drapes his hairy arm over the bin. Then he draws something upward, a brown, moist-edged paper bag. He shakes his head as he parts the paper packaging, drops the disappointment back in the bin and draws a slow, visible breath as he wipes his fingers on his chest. I warm my fingers on my coffee cup as I wonder when he last saw the horizon, what his mother’s name was, on which shore he left the love of his life, in order to chase a dream he thought she’d never understand.

The old man is initially defined by the curve of his spine. He’s bent almost double by some malady, and I feel the warm prickling of guilt as I watch him roll one sleeve up, and look over his shoulder. But I’m over the other shoulder, at a window seat in a busy cafe with another dozen pairs of averted eyes. He tilts his body like a crane and drapes his hairy arm over the bin. Then he draws something upward, a brown, moist-edged paper bag. He shakes his head as he parts the paper packaging, drops the disappointment back in the bin and draws a slow, visible breath as he wipes his fingers on his chest. I warm my fingers on my coffee cup as I wonder when he last saw the horizon, what his mother’s name was, on which shore he left the love of his life, in order to chase a dream he thought she’d never understand.